Fortunately it is frequently possible to translate literally and still retain contemporary

English idiom and excellent literary style. For example, “In the beginning

God created the heavens and the earth” is a straightforward translation of

the Hebrew text of Genesis 1:1, and it is also good English. So why change it? In

fact, why not follow this more literal approach everywhere and all the time, with

an absolute minimum of interpretation? Moisés Silva responds, “Translators who

view their work as pure renderings rather than interpretations only delude themselves;

indeed, if they could achieve some kind of noninterpretative rendering,

their work would be completely useless.”2 Daniel Taylor reinforces the point:

“All translation is interpretation, as George Steiner and others have pointed out.

At every point, the translator is required to interpret, evaluate, judge, and

choose.”3 Bob Sheehan correctly states that the “idea of a noninterpretive translation

is a mirage.”4

Several years ago I wrote about this very issue:

Translation without interpretation is an absolute impossibility,

for at every turn the translator is faced with interpretative decisions

in different manuscript readings, grammar, syntax, the

specific semantic possibilities of a Hebrew or Greek word for a

given context, English idiom, and the like. For example, should

a particular occurrence of the Hebrew word ,eres≥ be contextually

nuanced as “earth,” “land,” or something else? . . . In the

very act of deciding, the translator has interpreted.5

Moisés Silva further indicates the following:

A successful translation requires (1) mastery of the source language—

certainly a much more sophisticated knowledge than

one can acquire over a period of four or five years; (2) superb

interpretation skills and breadth of knowledge so as not to miss

the nuances of the original; and (3) a very high aptitude for

writing in the target language so as to express accurately both

the cognitive and the affective elements of the message.6

And biblical scholar Ephraim Speiser reminds us of the translator’s challenge:

The main task of a translator is to keep faith with two different

masters, one at the source and the other at the receiving

end. . . . If he is unduly swayed by the original, and substitutes

word for word rather than idiom for idiom, he is traducing

what he should be translating, to the detriment of both source

and target. And if he veers too far in the opposite direction, by

favoring the second medium at the expense of the first, the

result is a paraphrase.7

Speiser concludes by declaring that a “faithful translation is by no means the

same thing as a literal rendering.”8

Unfortunately, then, it is often not possible to translate literally and retain

natural, idiomatic, clear English. Consider the NASB rendering of Matthew

13:20: “The one on whom seed was sown on the rocky places, this is the man who

hears the word and immediately receives it with joy.” The NIV reads: “The one

who received the seed that fell on rocky places is the man who hears the word

and at once receives it with joy.” Here the NASB is so woodenly literal that the

result is a cumbersome, awkward, poorly constructed English sentence. The NIV,

on the other hand, has a natural and smooth style without sacrificing accuracy.

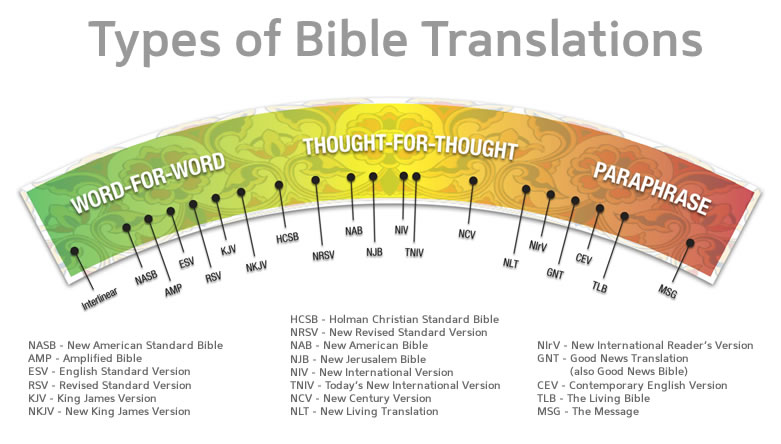

The second major type of translation is referred to variously as dynamic or

functional or idiomatic equivalence. Here the translator attempts a thought-forthought

rendering. The Good News Bible (GNB; also known as Today’s English

Version, TEV), the New Living Translation (NLT), God’s Word (GW), the

New Century Version (NCV), and the Contemporary English Version (CEV)

are some of the examples of this approach to the translation challenge. Such versions

seek to find the best modern cultural equivalent that will have the same

effect the original message had in its ancient cultures. Obviously this approach

is a much freer one.

At this point the reader may be surprised that the NIV has not been included

as an illustration of either of these two major types of translations. The reason is

that, in my opinion, it fits neither. After considerable personal study, comparison,

and analysis, I have become convinced that, in order to do justice to translations

like the NIV and the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), scholars must recognize

the validity of a third major category of translation, namely, the balanced

or mediating type. To discuss this subject intelligently, we must have a working

definition of formal equivalence and dynamic equivalence. Eugene Nida gives

us important insight:

Since “there are . . . no such things as identical equivalents,”

. . . one must in translation seek to find the closest possible

equivalent. However, there are fundamentally two different

types of equivalence: one which may be called formal and

another which is primarily dynamic.

Formal equivalence focuses attention on the message itself,

in both form and content. . . . Viewed from this formal orientation,

one is concerned that the message in the receptor language

should match as closely as possible the different

elements in the source language. This means . . . that the message

in the receptor culture is constantly compared with the

message in the source culture to determine standards of accuracy

and correctness.

The type of translation which most closely typifies this

structural equivalence might be called a “gloss translation,” in

which the translator attempts to reproduce as literally and

meaningfully as possible the form and content of the original.

. . . [Student] needs call for a relatively close approximation

to the structure of the early . . . text, both as to form (e.g., syntax

and idioms) and content (e.g., themes and concepts). Such a

translation would require numerous footnotes in order to make

the text fully comprehensible.

A gloss translation of this type is designed to permit the

reader to identify himself as fully as possible with a person in

the source-language context, and to understand as much as he

can of the customs, manner of thought, and means of expression.

For example, a phrase such as “holy kiss” (Romans 16:16)

in a gloss translation would be rendered literally, and would

probably be supplemented with a footnote explaining that this

was a customary method of greeting in New Testament times.

In contrast, a translation which attempts to produce a

dynamic rather than a formal equivalence is based upon “the

principle of equivalent effect.” . . . In such a translation one is

not so concerned with matching the receptor-language message

with the source-language message, but with the dynamic relationship

. . . , that the relationship between receptor and message

should be substantially the same as that which existed

between the original receptors and the message.

A translation of dynamic equivalence aims at complete naturalness

of expression and tries to relate the receptor to modes

of behavior relevant within the context of his own culture; it

does not insist that he understand the cultural patterns of the

source-language context in order to comprehend the message.

Of course, there are varying degrees of such dynamicequivalence

translations. . . . [Phillips, e.g.,] seeks for equivalent

effect. . . . In Romans 16:16 he quite naturally translates “greet

one another with a holy kiss” as “give one another a hearty

handshake all around.”

Between the two poles of translating (i.e., between strict formal

equivalence and complete dynamic equivalence) there are

a number of intervening grades, representing various acceptable

standards of literary translating.9

Edward L. Greenstein further describes the principle of dynamic equivalence

as proposing a “three-stage translation process: analysis of the expression in

the source language to determine its meaning, transfer of this meaning to the

target language, and restructuring of the meaning in the world of expression of

the target language.”10

Two observations may be helpful at this point. First, it is instructive that the

NIV retains “Greet one another with a holy kiss” in Romans 16:16. Second, it is

significant that Eugene Nida seems to open the door for a mediating position

between the two main translation philosophies, theories, or methods. In general

terms, all Bible translation is simply “the process of beginning with something

(written or oral) in one language (the source language) and expressing it in

another language (the receptor language).”11 A translation cannot be said to be

faithful that does not pay adequate attention to both the source language and the

receptor language.

A distinction must be made between dynamic equivalence as a translation

principle and dynamic equivalence as a translation philosophy. The latter exists

only when a version sets out to produce a dynamic-equivalence rendering from

start to finish, as the GNB did. The foreword to the Special Edition Good News

Bible indicates that word-for-word translation does not accurately convey the

force of the original, so the GNB uses instead the “dynamic equivalent,” the

words having the same force and meaning today as the original text had for its

first readers. Dynamic equivalence as a translation principle, on the other hand,

is used in varying degrees by all versions of the Bible.12 This is easily illustrated

by a few examples, several of which were given to me about 1990 by former Old

Testament professor (Calvin Theological Seminary) Dr. Marten Woudstra (now

deceased).

• A literal rendering of the opening part of the Hebrew text of Isaiah 40:2

would read, “Speak to the heart of Jerusalem.” Yet all English versions

(including the KJV) see the need for a dynamic-equivalence translation

here (e.g., the NIV has “Speak tenderly to Jerusalem”).

• In Jeremiah 2:2 the KJV and the NASB read “in the ears of Jerusalem,”

but the NKJV and the NIV have “in the hearing of Jerusalem.” Here

the NKJV is just as “dynamic” as the NIV. That it did not have to be is

clear from the NASB. Yet the translators wanted to communicate the

meaning in a natural way to modern readers, which is precisely what

the NIV also wanted to do.

• In Haggai 2:16 the NASB has “grain heap,” but the KJV, NKJV, and NIV

all use “heap” alone (which is all the Hebrew has). Here the formalequivalent

version, the NASB, is freer than the NIV.

• The KJV and the NKJV read “no power at all” in John 19:11, whereas

the NIV has only “no power” (in accord with the Greek). Which version

is following the formal-equivalence approach here, and which ones are

following the dynamic approach?

One could continue ad infinitum with this kind of illustration. Suffice it to mention

additionally that there is a book of over two hundred pages published as a

glossary to the oddities of the KJV word use and diction.13

In a similar vein, Ron Youngblood has written the following:To render the Greek word sarx by “flesh” virtually every

time it appears does not require the services of a translator; all

one needs is a dictionary (or, better yet, a computer). But to recognize

that sarx has differing connotations in different contexts,

that in addition to “flesh” it often means “human standards” or

“earthly descent” or “sinful nature” or “sexual impulse” or “person,”

etc., and therefore to translate sarx in a variety of ways is to

understand that translation is not only a mechanical, word-forword

process but also a nuanced [I would have said contextually

nuanced], thought-for-thought procedure. Translation, as

any expert in the field will readily admit, is just as much an art

as it is a science. Word-for-word translations typically demonstrate

great respect for the source language . . . but often pay only

lip service to the requirements of the target language. . . .

When translators of Scripture insist on reproducing every

lexical and grammatical element in their English renderings,

the results are often grotesque.14

Because I have served on the executive committee of the NIV’s Committee

on Bible Translation (CBT) since 1975 and have been the chief spokesperson for

the NIV, people often ask me, “What kind of translation, then, is the NIV?

Where does it fit among all the others?” While these related questions have been

dealt with generally in several publications and reviews, they are addressed

specifically in only one published authoritative source dating back to the release

of the complete NIV in 1978:

Broadly speaking, there are several methods of translation:

the concordant one, which ranges from literalism to the comparative

freedom of the King James Version and even more of

the Revised Standard Version, both of which follow the syntactical

structure of the Hebrew and Greek texts as far as is

compatible with good English; the paraphrastic one, in which

the translator restates the gist of the text in his own words; and

the method of equivalence, in which the translator seeks to

understand as fully as possible what the biblical writers had to

say (a criterion common, of course, to the careful use of any

method) and then tries to find its closest equivalent in contemporary

usage. In its more advanced form this is spoken of as

dynamic equivalence, in which the translator seeks to express

the meaning as the biblical writers would if they were writing

in English today. All these methods have their values when

responsibly used.As for the NIV, its method is an eclectic one with the emphasis

for the most part on a flexible use of concordance and equivalence,

but with a minimum of literalism, paraphrase, or outright

dynamic equivalence. In other words, the NIV stands on middle

ground—by no means the easiest position to occupy. It may

fairly be said that the translators were convinced that, through

long patience in seeking the right words, it is possible to attain

a high degree of faithfulness in putting into clear and idiomatic

English what the Hebrew and Greek texts say. Whatever literary

distinction the NIV has is the result of the persistence with

which this course was pursued.15

The CBT has also formulated certain guidelines in an unpublished document

(“Translators’ Manual,” dated 29 November 1968):

1. At every point the translation shall be faithful to the Word of God as represented

by the most accurate text of the original languages of Scripture.

2. The work shall not be a revision of another version but a fresh translation

from the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

3. The translation shall reflect clearly the unity and harmony of the Spiritinspired

writings.

4. The aim shall be to make the translation represent as clearly as possible

only what the original says, and not to inject additional elements by

unwarranted paraphrasing.

5. The translation shall be designed to communicate the truth of God’s

revelation as effectively as possible to English readers in the language of

the people. In this respect the Committee’s goal is that of doing for our

own times what the King James Version did for its day.

6. Every effort shall be made to achieve good English style.

7. The finished product shall be suitable for use in public worship, in the

study of the Word, and in devotional reading.

The following statements appear later in this same document:

1. Translators should keep the principles of the translation constantly in

mind and strive for accuracy, clarity, and force of expression.

2. Translators should do their work originally from the original language,

but before the completion of their work representative translations and

commentaries shall be consulted.

3. Certain notes of text variation, alternative translation, cross reference,

or explanation will be put in the margin.4. The purpose of the project is not to prepare a word-for-word translation

nor yet a paraphrase.

5. Read the passages as a whole and aloud to check for euphony and suitability

for public reading.

At the time of the NIV’s publication I wrote this about the translation work:

About two thousand years ago, when confronted with the

prospect of translating Plato’s Protagoras into Latin, Cicero

declared, “It is hard to preserve in a translation the charm of

expressions which in another language are most felicitous. . . . If

I render word for word, the result will sound uncouth, and if

compelled by necessity I alter anything in the order or wording,

I shall seem to have departed from the function of a translator.”

Such is the dilemma of all translators! And the problem is particularly

acute for those who attempt to translate the Bible, for it

is the eternal Word of God. The goal, of course, is to be as faithful

as possible in all renderings. But faithfulness is a doubleedged

sword, for true faithfulness in translation means being

faithful not only to the original language but also to the “target”

or “receptor” language. That is precisely what we attempted to

produce in the New International Version—just the right balance

between accuracy and the best contemporary idiom.16

In spite of that goal, I am certain that from time to time we will continue to be

criticized—by some for being literal but not contemporary enough, and by others

for being contemporary but not literal enough. Yet perhaps that fact in itself

will indicate that we have basically succeeded.

All this clearly indicates that the CBT attempted to make the NIV a balanced,

mediating version—one that would fall about halfway between the most

literal and the most free. But is that, in fact, where the NIV fits? Many neutral

parties believe so. For example, Steven Sheeley and Robert Nash state, “The NIV

committees attempted to walk this fine line and, to their credit, usually achieved

a good sense of balance between fidelity to the ancient texts and sensitivity to

modern expression.” They conclude, “Like any other modern translation of the

Bible, the NIV should not be considered the only true translation. Its great

achievement, though, lies in its readability. No other modern English translation

has reached the same level and still maintained such a close connection to the

ancient languages.”17

A similar opinion is expressed in the “Report to General Synod Abbotsford

1995” by the Committee on Bible Translations appointed by General Synod Lin-coln 1992 of the Canadian Reformed Churches. The members of the committee

(P. Aasman, J. Geertsema, W. Smouter, C. Van Dam, and G. H. Visscher) thoroughly

and carefully investigated the NASB, the NKJV, and the NIV. They indicated

that the NIV “attempted to strike a balance between a high degree of

faithfulness to the text and clarity for the receptor in the best possible English.”

They added that “it was frequently our experience that very often when our initial

reaction to an NIV translation was negative, further study and investigation

convinced us that the NIV translators had taken into account all the factors

involved and had actually rendered the best possible translation of the three versions.”

18 Similarly, when the committee questioned a passage as being too interpretive,

upon closer examination it was often discovered that the NIV had

produced a text that was accurate yet idiomatic.19 They concluded that “the NIV

is more idiomatic than the NASB and NKJV but at the same time as accurate as

the NASB and NKJV.”20 (By the way, the General Synod Abbotsford 1995 of the

Canadian Reformed Churches adopted these two recommendations—among

others: [1] to continue to recommend the NIV for use in the churches, and [2] to

continue to leave it in the freedom of the churches if they feel compelled to use

other translations that received favorable reviews in the reports.)

Another neutral voice is that of Terry White in an article about how a Baptist

General Conference church (Wooddale in Eden Prairie, Minnesota) endorsed

the NIV as the best translation for their membership. The church appointed a

task force to evaluate the NIV, the RSV, the NASB, and the NKJV. The NIV

came out ahead in nine of ten areas evaluated (most readable, best scholarship

used, best grammatically, best paragraphing, best concordances and supplemental

writing, best for use by laity, best Old Testament, best New Testament, and

best total Bible). A slight edge was given to the NASB as the most accurate rendering

of the original texts. Nonetheless it was clear that the NIV had the best

overall balance.21

Strictly speaking, then, the NIV is not a dynamic-equivalence translation.

If it were, it would read “snakes will no longer be dangerous” (GNB) instead of

“dust will be the serpent’s food” (Isa 65:25). Or it would read in 1 Samuel 20:30

“You bastard!” (GNB) instead of “You son of a perverse and rebellious woman!”

Similar illustrations could be multiplied to demonstrate that the NIV is an

idiomatically balanced translation.

How was such a balance achieved? By having a built-in system of checks

and balances. We called it the A–B–C–Ds of the NIV, using those letters as an

alphabetic acrostic to represent accuracy, beauty, clarity, and dignity. We wanted

to be accurate, that is, as faithful to the original text as possible (see our comments

on the rendering of Genesis 1:1 at the beginning of this chapter). But it wasimportant to be equally faithful to the target or receptor language—English in

this case. So we did not want to make the mistake—in the name of accuracy—

of creating “translation English” that would not be beautiful and natural. Accuracy,

then, must be balanced by beauty of language. The CBT attempted to make

the NIV read and flow the way any great English literature should. Calvin D.

Linton (professor emeritus of English at George Washington University) has

praised the beauty of the NIV as literature:

The NIV is filled with sensitive renderings of rhythms, from

the exultant beat of the Song of Deborah and Barak (Judg 5:1–

31) to the “dying fall” of the rhythms of the world-weary

Teacher in Ecclesiastes, with myriad effects in between. As a

random sample, let the reader speak the following lines from

Job (29:2–3), being careful to give full value to the difference

between stressed and unstressed syllables:

How I long for the months gone by,

for the days when God watched over me,

when his lamp shone upon my head

and by his light I walked through darkness!

It is better than the KJV!22

At the same time we did not want to make the mistake—in the name of

beauty—of creating lofty, flowery English that would not be clear. So beauty

must be balanced by clarity: “When a high percentage of people misunderstand

a rendering, it cannot be regarded as a legitimate translation.”23 If a translation

is to be both accurate and clear (idiomatic), it cannot be a mechanical exercise;

instead, it must be a highly nuanced process. Popular columnist Godfrey Smith

wrote in The Sunday Times (London, England):

I was won over by the way the new Bible [the NIV] handles

Paul’s magnificent [First] Epistle to the Corinthians [13:4].

“Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity

vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up.” So runs the old version

[the KJV], but the word charity is a real showstopper. The new

version puts it with admirable simplicity: “Love is patient, love

is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud.” The

old thunder has been lost, but the gain in sense is enormous.24

My favorite illustration of lack of clarity is the KJV rendering of Job 36:33:

“The noise thereof sheweth concerning it, the cattle also concerning the vapour.”

In the interest of clarity the NIV reads, “His [God’s] thunder announces the coming

storm; even the cattle make known its approach.” Or consider the Lord’sdescription of the leviathan in Job 41:12–14 (KJV): “I will not conceal his parts,

nor his power, nor his comely proportion. Who can discover the face of his garment?

or who can come to him with his double bridle? Who can open the doors

of his face? His teeth are terrible round about.” Again, in order to communicate

clearly in contemporary English idiom, the NIV translates as follows:

I will not fail to speak of his limbs,

his strength and his graceful form.

Who can strip off his outer coat?

Who would approach him with a bridle?

Who dares open the doors of his mouth,

ringed about with his fearsome teeth?

The importance of clarity in Bible translations is obvious. Yet, the CBT did

not want to make the mistake—in the name of clarity—of stooping to slang, vulgarisms,

street vernacular, and unnecessarily undignified language. Clarity, then,

must be balanced by dignity, particularly since one of our objectives was to produce

a general, all-church-use Bible. Some of the dynamic-equivalence versions are at

times unnecessarily undignified, as illustrated above in 1 Samuel 20:30.

Additional examples could be given. But the point is that when we produced

the NIV, we wanted accuracy, but not at the expense of beauty; we wanted beauty,

but not at the expense of clarity; and we wanted clarity, but not at the expense of

dignity. We wanted all these in a nice balance. Did we succeed? Rather than be

restricted to using descriptive terms like formal equivalence, dynamic equivalence,

paraphrase, and the like, in answering this question, it may be more helpful

to note the distinctions John Callow and John Beekman make between four

types of translations: highly literal, modified literal, idiomatic, and unduly free.

Their view can be diagrammed like this:25

In their classification system the NIV, in my opinion, contains primarily modified

literal and idiomatic renderings, though with a greater number of idiomatic

ones. To sum up, there is a need for a new category in classifying translations—

a classification I’d call a mediating position.

What, then, makes a good Bible translation? In my opinion, a good translation

will follow a balanced or mediating translation philosophy. Donald Burdick

puts it this way:

Chapter 2: Bible Translation Philosophies 61

Unacceptable

highly literal

Acceptable

modified literal idiomatic

Unacceptable

unduly freeA good translation is neither too much nor too little. It is neither

too slavish a reproduction of the Greek [and Hebrew], nor

is it too free in its handling of the original. It is neither too modern

and casual, nor is it too stilted and formal. It is not too much

like the KJV, nor does it depart too far from the time-honored

beauty and dignity of that seventeenth-century classic. In short,

the best translation is one that has avoided the extremes and has

achieved instead the balance that will appeal to the most people

for the longest period of time.26

An appropriate conclusion to this chapter is provided by Bible translation

specialist Bruce Metzger:

Translating the Bible is a never-ending task. As long as English

remains a living language it will continue to change, and

therefore new renderings of the Scriptures will be needed. Furthermore,

as other, and perhaps still more, ancient manuscripts

come to light, scholars will need to evaluate the history of the

scribal transmission of the original texts. And let it be said,

finally, alongside such developments in translating the Bible

there always remains the duty of all believers to translate the

teaching of Holy Writ into their personal lives.27

NOTES

1. This chapter is adapted from a similar one in Kenneth L. Barker, The Balance of

the NIV: What Makes a Good Translation (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1999), 41–55, 112–14.

Appreciation is hereby expressed to the publisher for permission to use some of that

material. I take great pleasure in presenting this chapter in honor of my dear friend and

esteemed colleague, Dr. Ronald Youngblood, on the occasion of his retirement at age

seventy. Ron and I have known each other since 1959. I have appreciated his valuable

contributions to the New International Version (NIV), The NIV Study Bible, and the

New International Reader’s Version (NIrV)—all of them being projects I’ve had the

enjoyable privilege of working on with him. God be praised!

2. Moisés Silva, God, Language, and Scripture (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1990), 134.

3. Daniel Taylor, “Confessions of a Bible Translator,” Books & Culture (November/

December 1995), 17.

4. Bob Sheehan, Which Version Now? (Sussex: Carey Publications, n.d.), 21.

5. Kenneth L. Barker, The Accuracy of the NIV (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996), 16–17.

6. Silva, God, Language, and Scripture, 134.

7. E. A. Speiser, Genesis, Anchor Bible (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1964), lxiii–lxiv.

8. Ibid., lxvi; see also Herbert M. Wolf, “Literal versus Accurate,” in The Making of

the NIV, ed. Kenneth L. Barker (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1991), 125–34, 165.

9. Eugene A. Nida, Toward a Science of Translating (Leiden: Brill, 1964), 159–60.

10. Edward L. Greenstein, “Theories of Modern Translation,” Prooftexts 3 (1983):

9–39; quoted by J. T. Barrera, The Jewish Bible and the Christian Bible, trans. W. G. E.

Watson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998): 126.

11. R. Elliott, “Bible Translation,” in Origin of the Bible, ed. Philip W. Comfort

(Wheaton, Ill.: Tyndale, 1992), 233.

12. See Cecil Hargreaves, A Translator’s Freedom (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1993).

13. Melvin E. Elliott, The Language of the King James Bible: A Glossary Explaining

Its Words and Expressions (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1967); see also Edwin H.

Palmer, “The KJV and the NIV,” in The Making of the NIV, 140–54, 165.

14. Ronald Youngblood, “The New International Version was published in 1978—

this is the story of why, and how,” The Standard (November 1988): 18. For an example of

such a “grotesque” rendering, see Bob Sheehan, Which Version Now? 19 (this latter work

is available from International Bible Society in Colorado Springs, Colorado).

15. The Story of the New International Version (New York: The New York International

Bible Society, 1978), 13 (italics mine).

16. Kenneth L. Barker, “An Insider Talks about the NIV,” Kindred Spirit (Fall 1978): 7.

17. Steven M. Sheeley and Robert N. Nash Jr., The Bible in English Translation

(Nashville: Abingdon, 1997), 44, 46.

18. “Report to General Synod Abbotsford 1995” from the Committee on Bible

Translations appointed by Synod Lincoln 1992 of the Canadian Reformed Churches, 16.

19. See “Report to General Synod Abbotsford 1995,” 169.

20. “Report to General Synod Abbotsford 1995,” 63.

21. See Terry White, “The Best Bible Version for Our Generation,” The Standard

(November 1988): 12–14.

22. Calvin D. Linton, “The Importance of Literary Style,” in The Making of the NIV, 30.

23. Eugene A. Nida and Charles R. Taber, The Theory and Practice of Translation

(Leiden: Brill, 1982), 2.

24. Quoted in A Bible for Today and Tomorrow (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989), 19.

25. John Callow and John Beekman, Translating the Word of God (Grand Rapids:

Zondervan, 1974), 23–24.

26. Donald W. Burdick, “At the Translator’s Table,” The [Cincinnati Christian] Seminary

Review 21 (March 1975): 44.

27. Bruce M. Metzger, “Handing Down the Bible Through the Ages: The Role of

Scribe and Translator,” Reformed Review 43 (Spring 1990): 170.