Thursday, April 30, 2015

PART 1: THE THEORY OF BIBLE TRANSLATION

Posted by Unknown on 4:47 PM in Arsip/Archive | Comments : 0

Moisés Silva offers personal reflections on an old Italian complaint

that translators are traitors in the sense that they always (and necessarily)

fall short of conveying the total meaning of a text in one language into another.

His personal struggle early on to translate into English all the rich nuances of

Spanish, his own first language, convinced him that any “literal” word-for-word

translation strategy will prove both impossible and ultimately unhelpful. As he

points out, even so-called literal Bible translations like the ESV reflect countless

interpretive decisions and departures from strict literalism. With literary sensitivity

Silva explains that a faithful translator is obliged to convey in clear and

readable form, not only the meanings of individual words and phrases, but something

also of the structure, rhythm, and emotive elements of the original text.

Ultimately the “accuracy” of a translation should be measured by the degree to

which a translator has achieved all of these things. Silva sees the good translator,

not as a traitor, then, but as someone who responsibly “transforms a text by transferring

it from one linguistic-cultural context to another.”

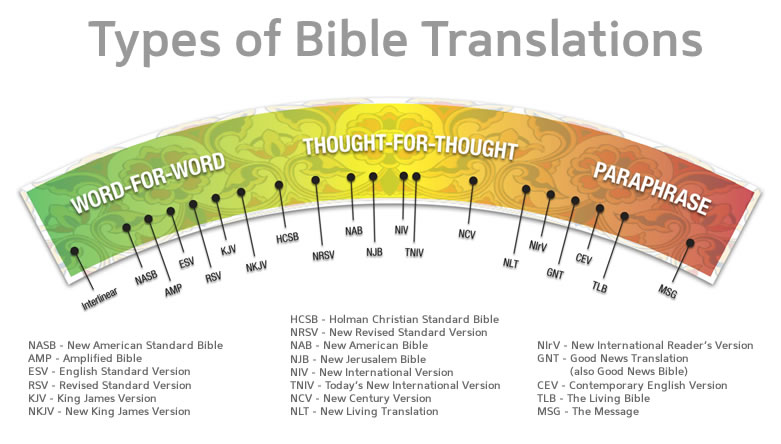

Kenneth Barker, longtime member of and spokesperson for the Committee

on Bible Translation, which has among its many translation achievements the

New International Version, sagely observes in chapter 2 that every group of Bible

translators must establish at the very outset the type of translation they intend to

produce. This in turn requires a conscious philosophical positioning of their

translation project. After emphatically rejecting as naive the possibility of meaningful

translation without at least some degree of interpretation, Barker

acknowledges that a group of translators may choose to pursue a philosophy that

leans either toward formal equivalence or toward dynamic equivalence. But he

argues that it is also possible to adopt a balanced or mediating translation philosophy

that combines the strengths of these respective options while avoiding

the weaknesses inherent in their more extreme forms. Barker presents the NIV

as an example of such optimal balance in its intentional pursuit of the four highly

desirable translation characteristics of accuracy, clarity, beauty, and dignity.

D. A. Carson (chapter 3) begins by noting two opposing trends in recent years:

(1) the virtual triumph of functional-equivalence theory across the scholarly disciplines

relevant to Bible translation, and (2) the contrasting rise of what he calls

“linguistic conservatism”—a popular movement with a strongly expressed preference

for more direct and “literal” translation methods. By pointedly challenging

a couple of representatives of this latter perspective, he builds his case for

functional equivalence as the only responsible approach to Bible translation for a

general readership. As he then points out, the ideological gulf between the practitioners

of these two competing approaches is nowhere more evident than in the

recent debate over gender-accurate language in Bible translation.

Carson devotes the remainder of his essay to sounding a caution on the limitations—

and even risks, when taken to excess—of functional-equivalence

theory. Responsible practitioners of functional equivalence will not make “reader

response” the supreme criterion in translation decision, nor will they concede the

skeptical assumption of an impassible dichotomy between message and meaning.

He calls for limits on a variety of other factors as well, from the pursuit of

comprehensibility and stylistic elegance at all costs to the dubious incorporation

of opinionated study notes in the published text of Scripture.

Mark Strauss addresses current issues in the gender-language

debate. The chapter is essentially a response to various charges leveled by Vern

Poythress and Wayne Grudem against recent gender-accurate Bible translations

(see The Gender-Neutral Bible Controversy: Muting the Masculinity of God’s Word

[2000]). Strauss begins by listing a surprising number of important areas of agreement

between the two sides—shared convictions about the nature of authoritative

Scripture, the translation enterprise, and even gender language itself.

Strauss then moves on to critical areas of disagreement between the two

camps. Most of these, he suggests, are rooted in different understandings of linguistics.

Throughout this section Strauss repeatedly concedes that the genderinclusive

approach may in some cases sacrifice some of the nuances of the original

text. But such losses, he insists, are unavoidable and “come with the territory” of

translation work. He urges the opponents of gender-inclusive translation to be

equally up-front about the dimensions of meaning they are compelled to sacrifice

through their approach. At the very least there should be a cessation on both sides

of emotive charges that the opposition is deliberately distorting the Word of God.

The late Herbert Wolf, a longtime member of the Committee on

Bible Translation, reflects from his own experiences on the communal dimensions

of translation. He begins with a carefully nuanced acknowledgment that

translators belong to larger communities and traditions that powerfully inform

and shape (but—and here he shows his epistemological optimism—need never

completely determine) their reading of the biblical text.

Wolf also sees great benefits in the fact that most recent translations of the

Bible have been group projects—not least that group arrangements enable translators

to pool strengths and purge idiosyncrasies; and here he speaks (as only an

experienced translation practitioner can) of the humbling aspect of having one’s

work tested and improved by peers. He also sees translation as communal in the

sense that it draws from related fields like archaeology and linguistics, a point

he illustrates with fascinating insights from the field of rhetorical criticism.

Finally, the potential readers of a translation also constitute a most relevant community,

inasmuch as responsible translation decisions will always factor in readers’

anticipated responses to the text.

In chapter 6 Charles Cosgrove reflects on the values that should inform and

the approach that should characterize a Bible translation methodology compatible

with the legitimate aspirations of postmodernism. The defining feature of

such a legitimate postmodern approach, he suggests, is best encapsulated in theadjective holistic. Under this rubric he first considers translating the Bible as a

whole (that is, as a canonical integrity), then translating the whole communicative

effect of Scripture (that is, its genre and medium, as well as its language), and

finally, translation as an activity of the whole people of God (the democratization

of translation).

Cosgrove’s first point—translating the Bible with canonical integrity—

raises such difficult issues as whether the translation of the Old Testament should

be guided in any way by how the New Testament purports to quote it. His second

point affirms the postmodern trend to “challenge traditional distinctions

between form and content and the hierarchy that subordinates one to the other.”

At the same time, he notes, the postmodern view is properly sensitive to the enormous

challenge (and downright trickiness) of achieving holistic equivalence in

any communication transfer between distinct cultural-linguistic systems. Finally,

Cosgrove argues that “the democratizing or ‘flattening’ cultural effect of postmodernity—

epitomized by the Internet” means that the age of officially authorized

versions is permanently over. He anticipates such a future scenario with

optimism, because he believes that the inevitable diffusion of translations will

only make the fullest sense of Scripture more accessible to all.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(

Atom

)

Post a Comment